Reaching true VR immersion: one blink at a time

The emergence of a truly immersive VR experience has long been awaited by those who keep close tabs on the VFX industry. In recent years, it could be argued that augmented reality (AR) has made the most meaningful gains, becoming ever more prevalent in everything from gaming to social media.

Yet interest in VR has not waned. It has simply been frustrated time and again by a set of key limitations. One of these is the challenge developers face in allowing people to move in a virtual environment.

“Many popular locomotion techniques used to date, such as teleportation, simply don’t provide the level of quality required to create the illusion in users that they are really exploring a virtual landscape,” Eike Langbehn, a doctoral candidate and research associate at the Human-Computer Interaction group at the University of Hamburg, told Foundry Trends.

Langbehn is author of a new paper introduced at SIGGRAPH - the world’s foremost VFX industry event - in Vancouver last week. What would really help bring the experience to life, he explains, is enabling people to simply find their way in the virtual world by walking.

“Walking is really the most natural form of locomotion, and it offers a lot of benefits. Users experience a higher sense of presence and better spatial knowledge within that environment, and - crucially - they are less likely to experience motion sickness - a common problem when devices such as gamepads and joysticks are used.”

Overcoming existing barriers

One major stumbling block here is that, barring those who can dedicate entire warehouses to VR, the real-world space in which users can walk tends to be highly constrained. As we explore in another article looking at the technical papers released at SIGGRAPH, existing techniques such as redirected walking (RDW) do allow for extended periods of walking.

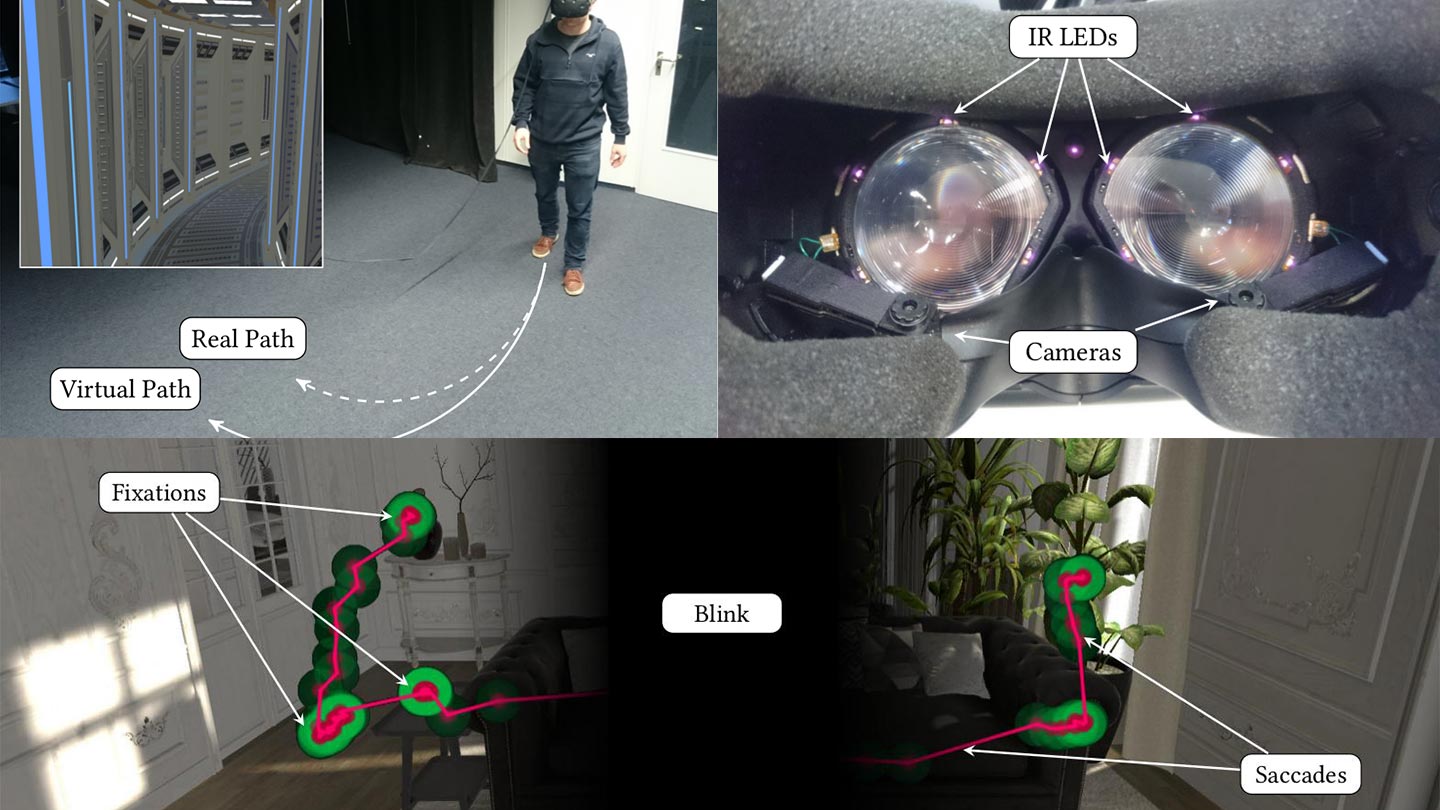

Langbehn and his colleagues were inspired by previous research on RDW that suggested exploiting brief moments when people are functionally blind, such as during saccades (when our eyes naturally make rapid movements between visual points), to rotate the VR landscape without that being detected by the user - maintaining the illusion of walking in a straight line but curving their actual path to keep them within the confines of the real world.

“We saw research from some colleagues that measured the amount of unnoticeable rotation it is possible to introduce during a saccade,” he added. “It then occurred to us that blinks might provide an even more opportune moment to make the rotations - they are easier to detect and last much longer.”

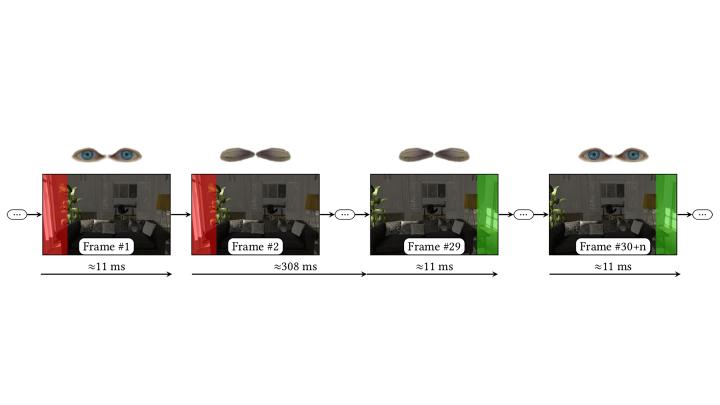

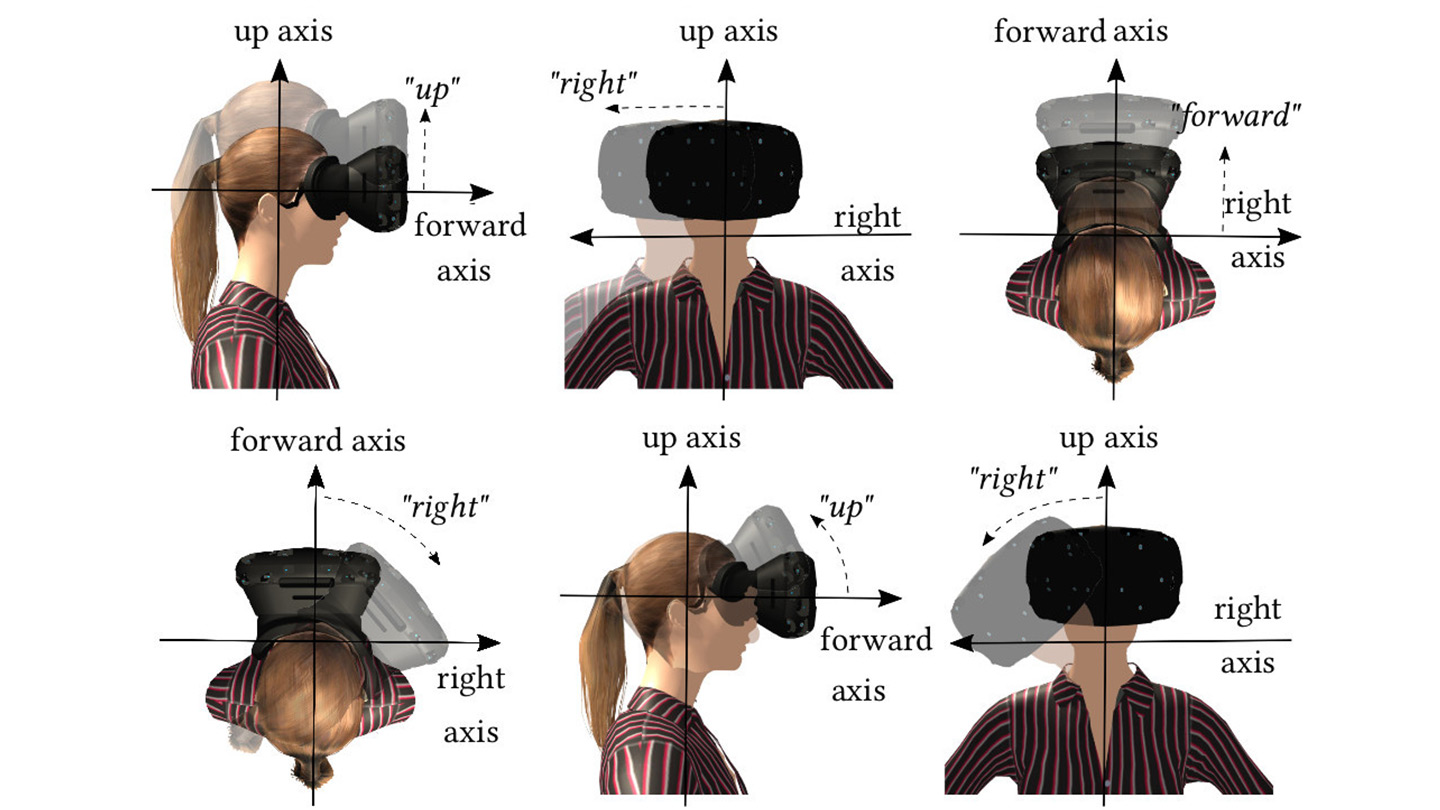

This is where advanced hardware comes in. An eye-tracker is integrated within a headset to follow the eye of the user. When the tracker fails to observe the presence of an eye for at least 300 milliseconds, a blink is ‘detected’, and the virtual camera is rotated or shifted. Langbehn found that rotations of approximately five degrees and translations of up to eight centimetres are not noticed by users, and can create a more seamless experience.

One small redirected step for the user, one giant leap for VR

It’s clear that there is still plenty of work to be done to make VR a deeply immersive experience, but this could be a significant move in that direction. Langbehn tells us that, while exploiting blinks alone will not be enough to enable unlimited walking in small tracking spaces, it certainly forms part of the solution.

“We showed that redirection during blinks can improve redirected walking by fifty percent. When combined with several other techniques, such as introducing redirection during saccades, smart path prediction and compression algorithms, it offers some wonderful experiences. In total, due to blinks and saccades, approximately 10 per cent of our whole visual input is suppressed. This has huge potential.”

The next steps will now have to take place, at least in part, on the hardware front. Current headsets generally don’t have built-in eye trackers. Other challenges on the hardware front also persist: most eye-trackers available for purchase tend to be highly expensive, bulky and prone to glitches.

The next generation of headsets, it is hoped, will go some way in resolving these issues. For the user, in the meanwhile, a little more patience will be required - but, if this breakthrough is anything to go by, it’ll be worth the wait.

Want to read more about how scientists are striving to create more immersive VR experiences? Check out our article on another paper showcased at this year's SIGGRAPH here.